Leveraging Object Detection Model for Power Savings in AR glasses

Authors:

Julie (Juhyun) Lee

Computer Science

juhy@cs.unc.edu

Ray Shealy

Computer Science

rbshealy@live.unc.edu

Introduction and Motivation

Augmented Reality glasses represent a transformative shift in how digital content is experienced and interacted with in real-world settings. Devices such as Meta Ray-Bans and Project Aria already include sophisticated sensing hardware—cameras, microphones, and inertial sensors—that allow for real-time perception and interaction. These devices are poised to support tasks like live AI assistance, translation, remote meetings, and immersive navigation. However, several technical challenges impede their practical adoption. These challenges include the need to last all day without recharging the battery, larger built-in displays, and increased neural computing efficiency inside of the glasses.

Among these, power efficiency is particularly critical. Unlike smartphones, AR glasses operate under stringent form factor limitations, severely constraining battery capacity. Yet, they must perform continuous rendering, environment sensing, and data processing. Traditional rendering pipelines refresh the display on a frame-by-frame basis, which can result in redundant computations when the scene or viewpoint changes little between frames.

To address this, we explore an approach that reuses rendered frames whenever possible in two different office productivity scenarios. We propose two models, one using object detection and the other using face detection, to estimate head motion and track the user’s gaze anchor point across time. When the displacement between frames falls below a set threshold, we infer that the scene is sufficiently stable and rendering can be skipped or minimized. This significantly reduces unnecessary computation and conserves energy.

Our work builds on prior research in adaptive rendering, motion-aware graphics, and computer vision-based tracking. Unlike model-based techniques requiring inertial measurements or depth sensors, our method relies solely on RGB data and bounding box inference from pretrained YOLO and FAN-Face models. We aim to evaluate how effective this minimal setup is in detecting usable frame stability across different workplace scenarios.

Related Work

The You Only Look Once (YOLO) family of models, including YOLOv5 and YOLOv8, are widely adopted for real-time object detection. YOLO introduced a paradigm shift by unifying bounding box regression and object classification into a single, end-to-end differentiable network. The architecture consists of three core components: a backbone for feature extraction, a neck for feature aggregation, and a head for final prediction. The backbone, typically a convolutional neural network (CNN), encodes input images into multi-scale feature maps. The neck further integrates and refines these features, while the head produces bounding box coordinates and class probabilities.

YOLOv5 incorporates several architectural enhancements to improve detection performance. Notably, it employs mosaic data augmentation by stitching multiple images together, enhancing robustness to small object detection. The feature extraction leverages Cross-Stage Partial Networks (CSP) modules, which split and merge feature maps to reduce computation while maintaining accuracy, drawing inspiration from DenseNet. Furthermore, YOLOv5 adopts the Path Aggregation Network (PANet) structure for improved multi-scale feature fusion. Its loss function is a composite of Binary Cross-Entropy (BCE) losses for classification and objectness, combined with Complete Intersection over Union (CIoU) loss for bounding box regression, optimizing directly for mean Average Precision (mAP).

YOLOv8 builds upon YOLOv5 with further architectural refinements. It introduces the C2f module, an evolution of the CSP layer, which enhances feature representation by fusing contextual and semantic information. Unlike previous YOLO versions, YOLOv8 adopts an anchor-free design and employs a decoupled head, allowing separate branches for objectness prediction, classification, and localization, leading to improved specialization and detection accuracy. In the output layer, a sigmoid activation is used for objectness scores, while a softmax activation computes class probabilities. For loss functions, YOLOv8 utilizes a combination of Complete IoU (CIoU) and Distribution Focal Loss (DFL) for localization, and BCE for classification, resulting in enhanced performance, particularly for small object detection.

Pose Estimation. Understanding a person’s posture and limb articulation is essential for high-level tasks such as action recognition. It also serves as a fundamental tool in fields like human-computer interaction (HCI) and animation. One of the earliest architectures proposed for pose estimation was the Stacked Hourglass network. This network follows a symmetric topology similar to U-Net, where features are progressively down-sampled to a very low resolution and then up-sampled, integrating information across multiple resolutions using convolutional neural networks. Unlike U-Net, which employs deconvolution layers for upsampling, the hourglass network utilizes nearest-neighbor upsampling of the lower-resolution features combined with skip connections via element-wise addition to perform top-down processing. This architecture achieved state-of-the-art (SOTA) performance on two standard pose estimation benchmarks at the time: FLIC and MPII Human Pose.

Face Alignment. For both 2D and 3D face alignment, the Face Alignment Network (FAN) model was proposed. This model is based on the Hourglass network but replaces the standard bottleneck block with a hierarchical, parallel, and multi-scale block, improving its effectiveness in face alignment tasks.

For face recognition, we utilized the FAN-Face model, which integrates two networks: the Face Alignment Network (FAN) and the Face Recognition Network (FRN). This combination enables more accurate face recognition by leveraging both spatial and identity-related features. In this approach, the heatmap generated by the pretrained FAN is concatenated with the input image and then fed into the Face Recognition Network. During training, feature tensors from both FAN and FRN are integrated. To enhance compatibility between these two feature representations, Adaptive Instance Normalization (AdaIN) is applied so that they have similar distributions. By incorporating heatmaps in addition to raw image inputs, the model incorporates spatial information and establishes landmarks, which enhances overall recognition accuracy. For training, they employed ArcFace loss. The model was trained using PyTorch and packaged as a Python module, which we utilized to extract precise nose tip coordinates from facial images.

Methods

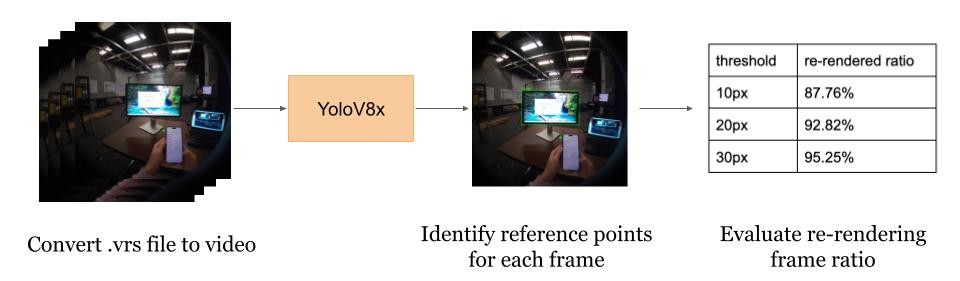

Object Detection Power Savings Pipeline for two monitor workplace scenario:

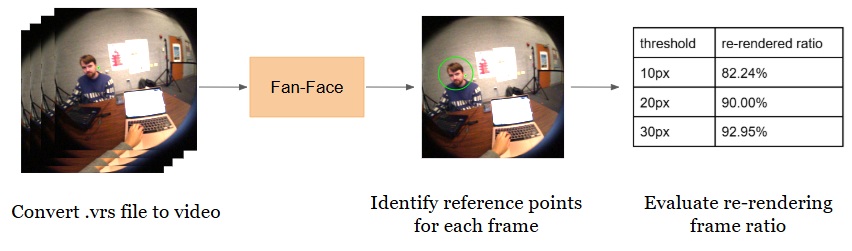

Object Detection Power Savings Pipeline for one-on-one meeting scenario:

These figures illustrate our proposed object detection power savings pipelines, which aim to reduce redundant computation by selectively re-rendering video frames. Given an input .vrs file from Project Aria, we first extract RGB video streams using the Aria Media Processing System (MPS). The video is then decomposed into individual frames using OpenCV. For each frame, YOLOv8x or FAN-Face are applied to detect the monitor or nose and extract reference point coordinates. These coordinates are subsequently compared across frames to estimate inter-frame pixel changes. Based on a predefined threshold, the system computes the proportion of frames that require re-rendering, resulting in a re-render frequency metric as the final output.

Data Collection

Our experimental data originates from a user wearing Meta Project Aria glasses while interacting with multiple monitors or other people in a workspace. The data were extracted from a .vrs file using Meta’s MPS processing pipeline, yielding two 5-minute RGB videos at 30 FPS, totaling a little over 9,000 frames each. Aria glasses have video resolution of 1408 x 1408 px.

Detection and Tracking Pipeline

For the monitor scenario, we used YOLOv8x, a state-of-the-art object detection model, to identify features labeled as tv, monitor, or screen. For each frame, we selected the top-right corner of the leftmost detected monitor as our gaze reference point. If no monitor was detected, we marked the coordinates as (-1, -1).

We introduced a preference function to ensure consistency in monitor selection when multiple monitors were visible, verifying its accuracy and consistency. The logic prioritized the leftmost bounding box among all qualifying detections to reduce tracking jitter.

For the one-on-one meeting (telepresence) scenario, we used FAN-Face, a face recognition model. For each frame, we selected the tip of the nose as our gaze reference point. If no nose was detected, we marked the coordinates as (-1, -1).

In situations where the nose is outside the image, the face does not need to be rendered in the AR glasses because the subject is not viewing the other person in the meeting. We choose to add these frames in our re-render calculation, classifying them as power saving opportunities.

Motion-Based Re-Render Decision

To evaluate the head movement between frames, we computed the Euclidean distance between the current frame’s reference coordinates (in pixels) and those of the last rendered frame. If the displacement was below a configurable threshold (10, 20, or 30 pixels), we skipped re-rendering. Otherwise, the frame was fully rendered and became the new reference.

To formalize this:

D(i) = sqrt((x_i - x_r)^2 + (y_i - y_r)^2)

where x_i and y_i are current coordinates while x_r and y_r are reference frame coordinates. If D(i) < T, reuse the previous frame where T denotes an arbitrarily defined threshold. Frames with invalid coordinates (i.e., -1, -1) were excluded from rendering and the re-render ratio calculation in the monitor scenario and included in the telepresence scenario.

Evaluation Metric

We define the re-render frequency R as: Lower values of R indicate greater rendering efficiency. We computed R under different thresholds (10, 20, 30 pixels) to analyze sensitivity and optimization potential. For example, R = 10% means ten percent of frames do NOT need to be re-rendered in the video, saving the power of rendering 900 frames (assuming 9000 total frames in a video).

Assumptions and Limitations

- In the one-on-one meeting scenario, we used the coordinates of the nose to determine whether to render the scene. However, a limitation of this approach is that, unlike the dual-monitor workspace scenario—where monitors remain stationary—the person in the meeting continues to move their body. As a result, even if the nose stays within the predefined threshold and the scene is not rendered, the person may still be moving their hands or body, meaning the scene needs to be re-rendered anyway. Nevertheless, our project only considered facial movement (trivial in this scenario) and did not take body movements into account.

- The method assumes the monitor presence in the field of view for all frames in the monitor workplace scenario. If no monitor is present, we conclude that the frame does not need to be re-rendered, and include it in our rendering frequency metric. In actuality, one monitor may need to be re-rendered while the other does not. However, we verified that both monitors were present in all frames of our collected data to make this assumption.

- No temporal smoothing was applied; minor detection jitter in our detection models may cause false positives by calculating a large jump between frames if multiple monitors are present. We manually verified this was not the case in each scenario.

- Lighting changes and occlusions can influence YOLO and FAN-Face detection accuracy. Specifically, movement of the other person’s head can make it harder to detect the nose or provide less accurate distance calculations. Likewise, glare from the monitors may detract from detection accuracy.

In future work, incorporating multi-object smoothing, confidence-weighted detection, or gaze estimation could improve robustness.

Experimental Result

| Threshold (px) | Monitor Scenario | Nose Scenario |

|---|---|---|

| 10 | 87.76% | 82.24% |

| 20 | 92.82% | 90.00% |

| 30 | 95.25% | 92.95% |

Table: Re-rendered ratio by threshold under different scenarios

Conclusion

In this work, we proposed a data-driven framework for optimizing rendering efficiency in augmented reality glasses by leveraging object and face detection models to track scene movements. We demonstrated that significant reductions in rendering frequency can be achieved by monitoring pixel displacement of reference points such as monitors and facial landmarks. Our experimental results show that with a reasonable threshold, more than 90% of frames can be reused without perceptible scene changes, indicating substantial potential for power savings.

While our approach focuses on gaze anchor stability and excludes broader body movements, it opens promising directions for future research. In particular, integrating temporal smoothing, richer motion cues, and semantic understanding of the scene could further enhance the robustness and applicability of rendering optimization strategies for AR devices. As energy efficiency remains a critical bottleneck for AR adoption, developing intelligent rendering control mechanisms such as ours is essential for enabling seamless, long-duration AR experiences in real-world environments.